As Damien Linnane says, receiving a letter in prison can be the difference between a good day and an awful one.

Linnane, who was formerly incarcerated and is the editor of the Paper Chained prison art journal, has seen firsthand how important letters are to those who are incarcerated.

“A little thing like getting a letter can completely change your day and even your week,” Linnane told About Time. “It really improves poor mental health, it alleviates boredom.

“Speaking from experience, the worst thing about prison is the lack of things to do. Writing was something I turned to. It really makes a huge difference to your sentence.”

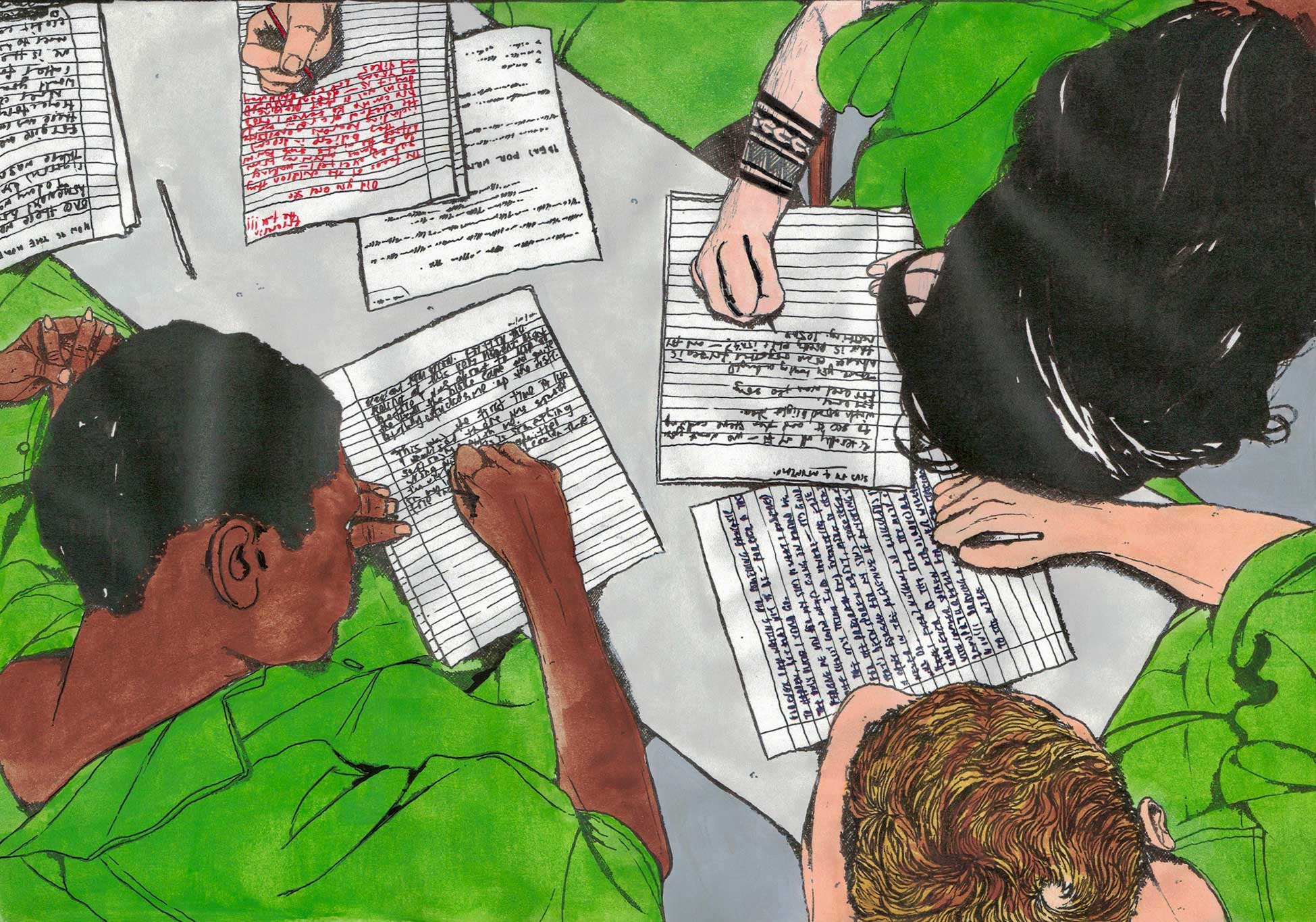

One way to help those in prison receive more letters and stay in contact with people in the outside community is through pen-pal programs which connect incarcerated people with those in the community.

Prison pen-pal programs have been found to be hugely popular and successful around the world, including in the United States, United Kingdom and New Zealand.

Prison pen-pal programs have been found to improve the health and wellbeing of those in prison, and their rehabilitation, thanks to improved connections with

the general community.

They are less common in Australia, where some prison authorities have barred participation in pen-pal programs or require express permission.

Nikita, a member of the Formerly Incarcerated Justice Advocates (FIGJAM) Collective, told About Time that sending and receiving letters while in prison is “extremely important. … because phone calls are so expensive, often people are left to just write letters to stay in contact with their family and friends.

“It’s important for mental health and community connections and family connections. It’s just a healthier experience, and you’re much more connected.”

Tens of thousands of people in the US and UK participate in prison pen-pal programs, some of which are either formally administered by prison authorities or at least actively encouraged.

The Hardman Trust operates the Prisoners’ Penfriends scheme in the UK, which involves about 200 people sending around 3,700 letters each year. The service is available across 90 prisons in England and Wales, with the organisation supervising the program and checking each letter.

A study into the scheme by the University of Warwick found that it improved wellbeing, giving early warning signs of potential self-harm and improved chances of successful rehabilitation.

A quarter of all people taking part in the program did not have any contact with other people in the community, and having a pen pal helped them to feel less isolated, happier and more likely to make changes to their self-identity.

As Damien Linnane says, receiving a letter in prison can be the difference between a good day and an awful one.

Linnane, who was formerly incarcerated and is the editor of the Paper Chained prison art journal, has seen firsthand how important letters are to those who are incarcerated.

“A little thing like getting a letter can completely change your day and even your week,” Linnane told About Time. “It really improves poor mental health, it alleviates boredom.

“Speaking from experience, the worst thing about prison is the lack of things to do. Writing was something I turned to. It really makes a huge difference to your sentence.”

One way to help those in prison receive more letters and stay in contact with people in the outside community is through pen-pal programs which connect incarcerated people with those in the community.

Prison pen-pal programs have been found to be hugely popular and successful around the world, including in the United States, United Kingdom and New Zealand.

Prison pen-pal programs have been found to improve the health and wellbeing of those in prison, and their rehabilitation, thanks to improved connections with

the general community.

They are less common in Australia, where some prison authorities have barred participation in pen-pal programs or require express permission.

Nikita, a member of the Formerly Incarcerated Justice Advocates (FIGJAM) Collective, told About Time that sending and receiving letters while in prison is “extremely important. … because phone calls are so expensive, often people are left to just write letters to stay in contact with their family and friends.

“It’s important for mental health and community connections and family connections. It’s just a healthier experience, and you’re much more connected.”

Tens of thousands of people in the US and UK participate in prison pen-pal programs, some of which are either formally administered by prison authorities or at least actively encouraged.

The Hardman Trust operates the Prisoners’ Penfriends scheme in the UK, which involves about 200 people sending around 3,700 letters each year. The service is available across 90 prisons in England and Wales, with the organisation supervising the program and checking each letter.

A study into the scheme by the University of Warwick found that it improved wellbeing, giving early warning signs of potential self-harm and improved chances of successful rehabilitation.

A quarter of all people taking part in the program did not have any contact with other people in the community, and having a pen pal helped them to feel less isolated, happier and more likely to make changes to their self-identity.

There are numerous prison pen-pal programs across the United States, including the Wire of Hope.

The Prisoner Correspondence Network Aotearoa in New Zealand has been running since 2016. It is the largest pen-pal network in the country, with more than 5,000 members.

In Victoria, people who are incarcerated must obtain permission from the prison general manager to participate in a pen-pal program, and will be allowed to do so only in “exceptional circumstances”.

“In exceptional circumstances, certain prisoners without connections in the community may be able to apply for a pen-pal program,” a spokesperson for the Victorian Department of Justice and Community Safety told About Time.

“As part of Corrections Victoria’s strict security measures, incoming and outgoing mail is subject to scanning and checks.”

There are less clear rules around prison pen-pal programs in the other Australian states and territories, although there are no formal or encouraged programs around the country.

Prison regulations in New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia do not mention prison pen-pal programs at all, in contrast to Victoria.

Linnane previously ran an informal pen-pal program for those in prison through his newsletter, which led to it being banned in several prisons in Queensland and Victoria, and removed from tablets in New South Wales prisons.

The NSW ban was believed to be about concerns people on protection were communicating with those not on protection in prison.

Linnane said he was eventually able to have these bans overturned when he removed the pen-pal program from the newsletter entirely.

“I don’t know of any other place in the world that has a ban on pen-pal programs,” Linnane said. “In the UK and US, prison pen-pal programs are actually actively encouraged.”

There have been campaigns for Victoria to overturn its ban on pen-pal programs, and for other states and territories to more actively encourage and facilitate these schemes.

“I think there’s a lot to lose by depriving prisoners of that support,” Linnane said. “It’s something that can improve mental health, and anything that improves mental health can reduce violence, self-harm and strains on the prison system.”

There are numerous prison pen-pal programs across the United States, including the Wire of Hope.

The Prisoner Correspondence Network Aotearoa in New Zealand has been running since 2016. It is the largest pen-pal network in the country, with more than 5,000 members.

In Victoria, people who are incarcerated must obtain permission from the prison general manager to participate in a pen-pal program, and will be allowed to do so only in “exceptional circumstances”.

“In exceptional circumstances, certain prisoners without connections in the community may be able to apply for a pen-pal program,” a spokesperson for the Victorian Department of Justice and Community Safety told About Time.

“As part of Corrections Victoria’s strict security measures, incoming and outgoing mail is subject to scanning and checks.”

There are less clear rules around prison pen-pal programs in the other Australian states and territories, although there are no formal or encouraged programs around the country.

Prison regulations in New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia do not mention prison pen-pal programs at all, in contrast to Victoria.

Linnane previously ran an informal pen-pal program for those in prison through his newsletter, which led to it being banned in several prisons in Queensland and Victoria, and removed from tablets in New South Wales prisons.

The NSW ban was believed to be about concerns people on protection were communicating with those not on protection in prison.

Linnane said he was eventually able to have these bans overturned when he removed the pen-pal program from the newsletter entirely.

“I don’t know of any other place in the world that has a ban on pen-pal programs,” Linnane said. “In the UK and US, prison pen-pal programs are actually actively encouraged.”

There have been campaigns for Victoria to overturn its ban on pen-pal programs, and for other states and territories to more actively encourage and facilitate these schemes.

“I think there’s a lot to lose by depriving prisoners of that support,” Linnane said. “It’s something that can improve mental health, and anything that improves mental health can reduce violence, self-harm and strains on the prison system.”

A remote WA prison holding mostly First Nations people is “unfit for purpose”, with people sleeping on the floors and cockroach infestations.

A number of Victorian prisons may have to be renovated or rebuilt after the Supreme Court found that no “open air” was being provided to inmates in multiple units.

The Liberal Queensland government has announced plans to significantly minimise the rights to vote for people in prison.

The death of a 16-year-old First Nations teenager in a notorious youth unit of an adult prison in Western Australia was preventable and predictable, and the result of “serious longstanding deficiencies in the system, a Coroner has found.

Help keep the momentum going. All donations will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

All donations of $2 or more are tax deductible. If you would like to pay directly into our bank account to avoid the processing fee, please contact donate@abouttime.org.au. ABN 67 667 331 106.

Help us get About Time off the ground. All donations are tax deductible and will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

Your browser window currently does not have enough height, or is zoomed in too far to view our website content correctly. Once the window reaches the minimum required height or zoom percentage, the content will display automatically.

Alternatively, you can learn more via the links below.

Leave a Comment

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere. uis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.