This article contains references to an Indigenous Australian who has died, and references to suicide.

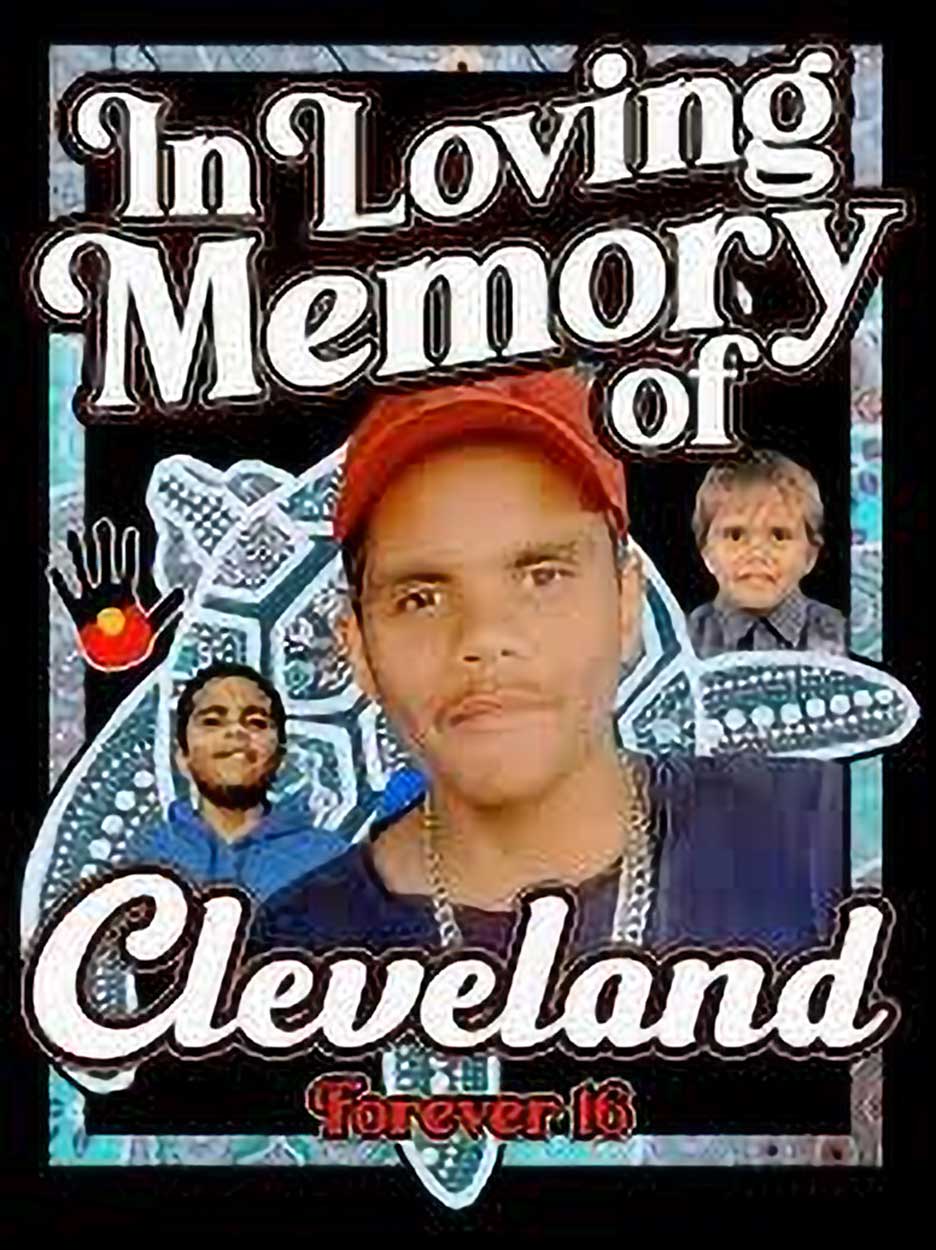

The death of a 16-year-old First Nations teenager in a notorious youth unit of an adult prison in Western Australia was preventable and predictable, and the result of “serious longstanding deficiencies in the system, a Coroner has found.

WA Coroner Phil Urquhart handed down his findings from the coronial inquest into the death of Cleveland Dodd in mid-October 2023, at the Unit 18 youth detention centre within the adult Casaurina Prison.

He found that the treatment of Cleveland before his death was “not only entirely inappropriate, but inhumane”, and that Unit 18 should be closed “as a matter of urgency”.

The Coroner also called for an inquiry to be held into how Unit 18 came to be established as the state’s second youth justice facility.

The Coroner found that for 74 of Cleveland’s last 87 days in custody he had been locked in his cell for longer than 22 hours each day, amounting to solitary confinement under international law.

“No child in detention deserves to be treated in the way Cleveland and the other young people in Unit 18 were treated at the time he decided to end

his life,” the Coroner said.

The death of a 16-year-old First Nations teenager in a notorious youth unit of an adult prison in Western Australia was preventable and predictable, and the result of “serious longstanding deficiencies in the system, a Coroner has found.

WA Coroner Phil Urquhart handed down his findings from the coronial inquest into the death of Cleveland Dodd in mid-October 2023, at the Unit 18 youth detention centre within the adult Casaurina Prison.

He found that the treatment of Cleveland before his death was “not only entirely inappropriate, but inhumane”, and that Unit 18 should be closed “as a matter of urgency”.

The Coroner also called for an inquiry to be held into how Unit 18 came to be established as the state’s second youth justice facility.

The Coroner found that for 74 of Cleveland’s last 87 days in custody he had been locked in his cell for longer than 22 hours each day, amounting to solitary confinement under international law.

“No child in detention deserves to be treated in the way Cleveland and the other young people in Unit 18 were treated at the time he decided to end

his life,” the Coroner said.

For Cleveland and other children held at Unit 18, prolonged periods of solitary confinement, isolation, intense boredom, meals eaten alone and a lack of access to mental health services, education and running water had become the norm, the Coroner found.

“The youth justice system failed Cleveland,” Urquhart said.

“It should never be forgotten that detainees are not only children but are some of the most vulnerable children in our state; many of whom have intellectual disabilities that can be directly linked to not only their offending in the community, but also to their behaviour when they are placed in detention.”

The Coroner made 15 adverse findings against the WA Department of Justice and a number of recommendations. He said that “tinkering at the edges” isn’t going to solve the problems, and that “wholesale reform and a complete reset is necessary”.

Cleveland’s mother told the inquest the impact his death has had on their family.

“My son’s death will not be in vain,” she said.

“In his memory, I must remain stalwart to change, to a kinder world and solid in the pursuit of justice even in the strongest winds.

“I hope that this process, which is unimaginably difficult for me and my family and indeed all those who loved Cleveland, will be the catalyst for real and lasting change. Enough is enough.

“My son didn’t deserve to be treated that way. My son didn’t deserve to die. I want justice for Cleveland.”

For Cleveland and other children held at Unit 18, prolonged periods of solitary confinement, isolation, intense boredom, meals eaten alone and a lack of access to mental health services, education and running water had become the norm, the Coroner found.

“The youth justice system failed Cleveland,” Urquhart said.

“It should never be forgotten that detainees are not only children but are some of the most vulnerable children in our state; many of whom have intellectual disabilities that can be directly linked to not only their offending in the community, but also to their behaviour when they are placed in detention.”

The Coroner made 15 adverse findings against the WA Department of Justice and a number of recommendations. He said that “tinkering at the edges” isn’t going to solve the problems, and that “wholesale reform and a complete reset is necessary”.

Cleveland’s mother told the inquest the impact his death has had on their family.

“My son’s death will not be in vain,” she said.

“In his memory, I must remain stalwart to change, to a kinder world and solid in the pursuit of justice even in the strongest winds.

“I hope that this process, which is unimaginably difficult for me and my family and indeed all those who loved Cleveland, will be the catalyst for real and lasting change. Enough is enough.

“My son didn’t deserve to be treated that way. My son didn’t deserve to die. I want justice for Cleveland.”

More than eight years since Ravenhall prison opened, recidivism rates at the prison are higher than those at public prisons.

An Ombudsman investigation has found people in Canberra’s only prison paid nearly $125,000 to make phone calls across two years when this should have been free.

Should going to prison mean never being allowed to hug your partner or child? Is denying physical contact a just punishment, or does it harm families and human dignity? And what do human rights have to say about it?

While for the most part calls to mobiles are becoming cheaper, we clearly still have a long way to go.

Help keep the momentum going. All donations will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

All donations of $2 or more are tax deductible. If you would like to pay directly into our bank account to avoid the processing fee, please contact donate@abouttime.org.au. ABN 67 667 331 106.

Help us get About Time off the ground. All donations are tax deductible and will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

Your browser window currently does not have enough height, or is zoomed in too far to view our website content correctly. Once the window reaches the minimum required height or zoom percentage, the content will display automatically.

Alternatively, you can learn more via the links below.

Leave a Comment

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere. uis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.